Fagfellevurdert

Effect of Myofascial Therapy After Surgery and Radiotherapy in Breast Cancer Treatment

Scientific article

Cecilie Erga, fysioterapeut, MHS, PhD kandidat, SHARE-senter for kvalitet og sikkerhet i helsetjenesten, Universitetet i Stavanger. cecilie.erga@uis.no.

Ingvild Dalen, biostatistiker, PhD Forskningsavdelingen, Stavanger universitetssjukehus.

Ylva Hivand Hiorth, spesialist i nevrologisk fysioterapi MNFF, PhD, Avdeling for fysikalsk medisin og rehabilitering og Senter for bevegelsesforstyrrelser, Stavanger universitetssjukehus.

Denne vitenskapelige artikkelen er fagfellevurdert etter Fysioterapeutens retningslinjer, og ble akseptert 10.januar 2025. Ingen interessekonflikter oppgitt.

Abstract

Purpose: Many women experience physical late effects after surgery and radiotherapy as part of breast cancer treatment and need physiotherapy. Myofascial therapy is a commonly used treatment for these late effects, though scientific evidence is limited. This systematic review aimed to evaluate and summarize the existing research on the effects of myofascial therapy on physical late effects after breast cancer treatment with surgery and radiotherapy.

Method: Systematic literature searches for randomized controlled trials investigating the effect of myofascial therapy on late effects after breast cancer were conducted in the databases Amed, Embase, Cinahl, Medline, PEDro, and Pubmed on February 27th, 2020, and February 6th, 2023. The Cochrane Collaboration ́s tool for assessing risk of bias (RoB) was used. Meta-analyses of outcome measures on shoulder abduction and flexion (degrees), shoulder function (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire, 0-100), and pain (log-transformed visual analogue scale, 0-100) were conducted to estimate mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: 233 studies were identified, of which five were included in the meta-analyses with 245 participants. Myofascial therapy improved shoulder abduction immediately after intervention (13.0; 6.3 to 19.6; p=0.001) and at last follow-up (10.4; 3.0 to 17.8; p=0.006), improved shoulder function at last follow up (-5.8; -10.7 to -1.0; p=0.020), and reduced pain intensity at last follow up (-0.33; -0.54 to -0.12; p=0.003).

Conclusion: This review indicates that myofascial therapy can have positive impact on late effects after breast cancer treatment regarding, shoulder abduction, shoulder function, and pain. More studies are needed to compare myofascial therapy with relevant alternative interventions, as well as investigating long-term effects, timing, frequency and duration of myofascial therapy, and other outcomes such as quality of life.

Key words: Breast cancer, myofascial treatment, late effects, physiotherapy.

Sammendrag

Effekt av myofascial terapi etter brystkreftbehandling med kirurgi og stråling

Hensikt: Flere kvinner lever med fysiske senskader etter kirurgi og stråling i forbindelse med brystkreftbehandling. Mange trenger fysioterapibehandling. Myofascial terapi er en flittig brukt behandlingsform, men det vitenskapelige kunnskapsgrunnlaget er begrenset. Hensikten med denne systematiske oversikten var å evaluere og sammenfatte eksisterende forskningslitteratur om effekt av myofascial terapi på fysiske senskader etter brystkreftbehandling med kirurgi og strålebehandling.

Design, materiale og metode: Systematiske litteratursøk etter randomiserte kontrollerte studier om effekten av myofascial terapi ved senskader etter brystkreft ble utført i databasene Amed, Embase, Cinahl, Medline, PEDro og Pubmed 27. februar 2020 og 6. februar 2023. For risikovurdering av systematiske skjevheter ble The Cochrane Collaboration ́s tool for assessing risk of bias (RoB) anvendt. Metaanalyser av utfallsmålene skulderabduksjon og skulderfleksjon (grader), skulderfunksjon (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire, 0-100), og smerte (log-transformert visual analog scale, 0-100) ble utført for å estimere gjennomsnittlige forskjeller med 95 % konfidensintervall.

Resultater: 233 artikler ble identifisert, hvorav fem ble inkludert i metaanalysene med 245 deltakere. Resultatene viser at myofascial terapi forbedret skulderabduksjon umiddelbart etter intervensjon (13,0; 6,3 til 19,6; p=0,001) og ved siste oppfølging (10.4; 3.0 to 17.8; p=0.006), forbedret skulderfunksjon ved siste oppfølging (-5,8; -10,7 til -1,0; p=0,020) og reduserte smerteintensitet ved siste oppfølging (-0.33; -0,54 til -0.12; p=0,003). Vi fant ikke at myofascial terapi forbedret skulderfleksjon.

Konklusjon: Studien indikerer at myofascial terapi kan ha positiv effekt på senskader etter brystkreftbehandling når det gjelder skulderabduksjon, skulderfunksjon og smerte. Det er behov for flere studier som sammenligner myofascial terapi med relevante kontrollintervensjoner, samt forskning på langtidseffekt, timing, frekvens og varighet av myofascial terapi, og studier som undersøker andre utfallsmål, eksempelvis livskvalitet.

Nøkkelord: brystkreft, myofascial behandling, senskader, fysioterapi.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common type of cancer in women worldwide. Due to improvements in diagnostic and treatment methods, BC has one of the highest survival rates among cancers (1–3). Consequentially, many women experience physical late effects in the cancerous upper body region after surgery and radiotherapy. These effects include skin changes, tissue adherence, lymphoedema, and nerve damage, resulting in shoulder- and upper-limb dysfunction and persisting pain (4–9). Myofascial therapy (MFT) is a commonly used physiotherapy modality for treating these late effects. MFT is a low load manual treatment, where slow, sustaining pressure is applied directly or indirectly to the areas of the skin that is restricted after radiotherapy and surgery (10). The purpose of MFT is to enhance fascia elastic properties in the radiated- and surgically affected area, improving conditions in tight skin and underlying soft tissue (10). While the Norwegian physiotherapy union guidelines acknowledge MFT as complementary to exercise for late effects after BC treatment, the current research on its effectiveness is insufficient (11), and the parameters for optimal MFT treatment intensity, application technique, amount of manual contact, and treatment settings are unclear (12). This systematic review aims to investigate the evidence for MFT effectiveness in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for preventing, reducing late physical effects in the affected upper body following BC treatment.

Methods

Search strategy

We systematically searched Amed, Cinahl, Embase, Medline, PEDro and Pubmed, limiting results to English, RCTs, human studies, and publications from 2009 onward to reflect recent advances in BC diagnostics and treatment (9). Population of interest was participants with BC diagnosis whose cancer treatment involved surgery and radiotherapy. There were no limitations regarding age, gender, surgical methods, radiation dose or -area. Intervention of interest was exclusively manual MFT treatment of soft tissue performed in the surgical affected and radiated areas. Comparison or outcome were not specified. Search terms and synonyms (not specified here) were “breast cancer”, “late effects”, “surgery”, “radiotherapy”, “myofascial therapy”, and “soft tissue”. Searches were performed by two independent investigators (C.E. and Y.H.H.) on February 27th, 2020, and February 6th, 2023, where the last search provided no additional studies eligible for inclusion. We conducted hand-searches in articles retrieved through database searches, texts and other reviews, contacted a foreign expert for further information and searched at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ and https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Study Selection and Eligibility

The selection of potential articles was done by two independent persons (C.E. and Y.H.H.) for verification of content and eligibility. Disagreements were solved by discussion until consensus was reached. After database searches were completed, duplicates were removed. Selection was firstly based on title and abstract, and final selection was based on full text. We excluded studies if participants had not had surgery and radiotherapy or did not receive MFT directed towards the affected areas of the body.

Data Collection and Analyses

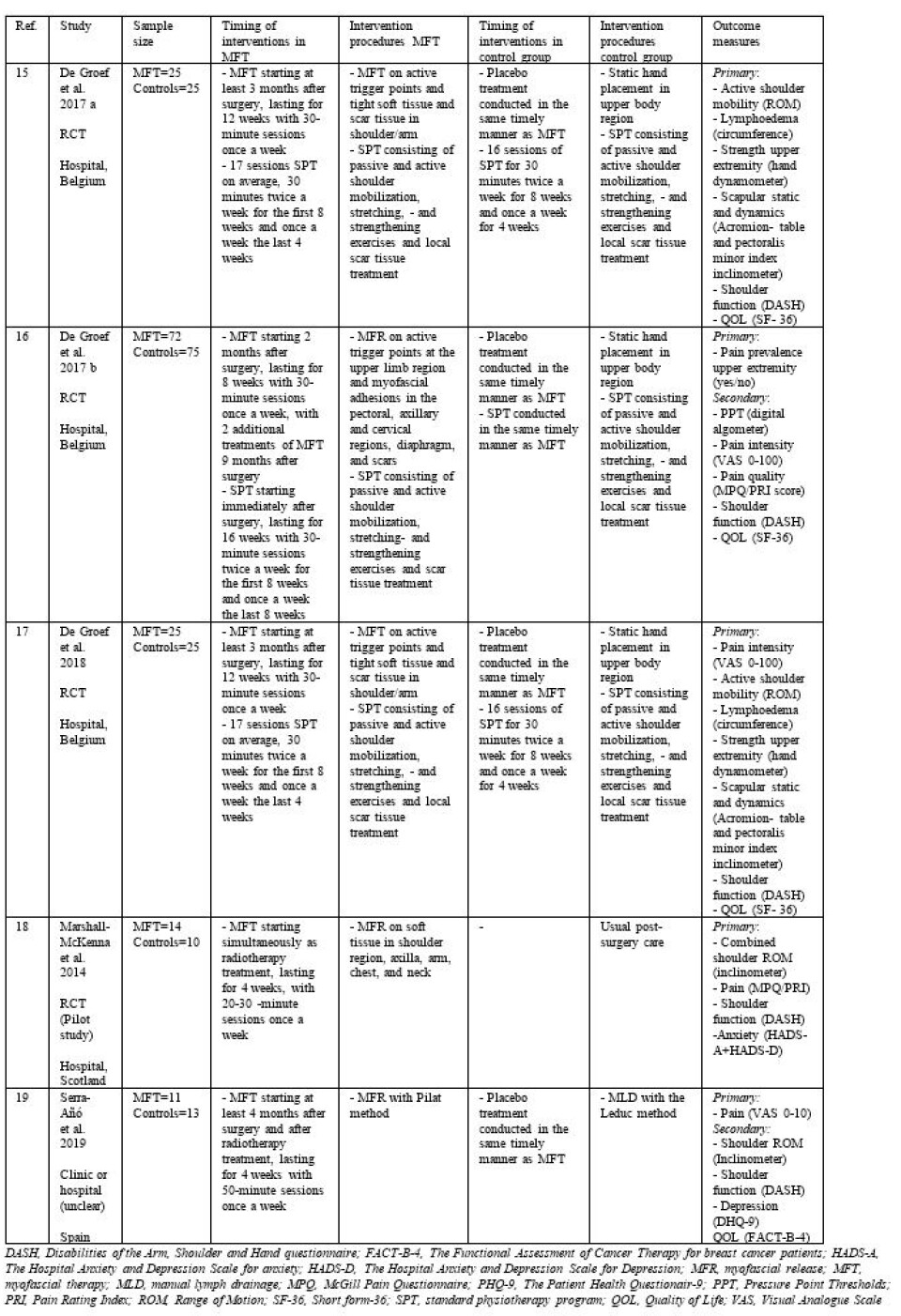

The authors (C.E., I.D., Y.H.H.) compiled data from the included studies into a table (Table 1) with information on author, year, design, setting, population, sample size, intervention received by MFT- group and control group, outcomes, and tools used for measuring outcomes. Meta-analyses of the effect of MFT on selected outcome measures were performed using software Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

The effect measure was the mean difference in outcome between treatment and control group. Due to differences in treatment length and timing, we applied random effects meta-analyses using the inverse variance method. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, which estimates the percentage of between-study heterogeneity which can be attributed to variability in the true treatment effect and tested using the χ2 test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Skewed variables were analysed on a log transformed scale using the method suggested by Higgins et al (13). Two separate analyses were performed for each outcome; (1) the immediate effect after the intervention, and (2) the sustained effect based on data from the longest follow-up assessment. Forest plots of the estimated effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to visualize the results, with the weight of each point estimate indicated by the relative size of the marker.

Quality assessment

Quality assessments were conducted by two independent assessors (C.E. and Y.H.H). Risk of bias in each study was performed using The Cochrane Collaboration ́s tool for assessing risk of bias (RoB). This tool assesses risk of bias within seven domains regarding randomization and allocation of participants, blinding of participants and therapists, adequate handling of incomplete outcome data, reports of outcome measures as planned, and other potential risk of bias where each domain is graded as high, low or unclear (14).

Data availability

Data that support this study are available from the corresponding author, (C.E.), on request.

Results

Results of the search

233 articles were identified through database searches and one additional article (15) was identified via hand search. After removing duplicates and screening articles for eligibility by title and abstract, ten remaining articles was left to be fully read, and five of these (15–19) were included in the present review. We excluded six articles (20–25), that did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Studies Included

Two of the included articles (15,17) report on different outcomes from the same study, hence, four randomized parallel-group controlled trials were included in this review, of which two studies (15–17) were conducted in Belgium, one (18) in Ireland, and one (19) in Spain. All studies were conducted in a natural setting, either in a clinic or a hospital by experienced therapists performing the treatments. Two (16,18) of the studies investigated the effect of MFT during the participants radiotherapy treatments. Two (15,17,19) of the studies investigated effect of MFT after the patients radiotherapy treatment was finished.

Study Characteristics

In total, 245 female participants diagnosed with breast cancer were included in the four trials, with 124 participants receiving MFT (age 53 to 63), and 121 controls (age 51 to 55).

Interventions

The interventions are described in Table 1. All studies measured effect of MFT on physical late effects in upper body using myofascial release (10) as technique. The treatment periods lasted from 4 to 12 weeks, where MFT was given once a week in all studies. The sessions lasted 30 minutes in all studies, except for one (19), where the treatment session lasted for 50 minutes. The controls in two studies (15–17) received placebo treatment using static hand placement on upper body, controls in one study (19) received manual lymph drainage and controls in one study (18) received no physiotherapy treatment. The participants in two (15–17) of the studies received standard physiotherapy in addition to MFT.

TABLE 1: Characteristics of included studies

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included shoulder range of motion (ROM), shoulder function, and pain intensity. All studies measured outcomes before and after the intervention period. Timing of follow up measures ranged from one to nine months after intervention. Three studies (15,18,19) assessed the effect of MFT om active shoulder ROMs (abduction and flexion) and reported in degrees (more is better). All studies used the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (DASH) to measure shoulder function. This scale ranges from 0-100 with higher scores signifying poorer function. Four studies (16–19) assessed the effect of MFT on pain intensity. Three of these studies (16,17,19) used Visual Analog Scale (VAS) as measurement tool, on a range of 0-100 with higher scores indicating more pain. The scores from the study by Serra-Añó et al. (19) which used VAS scale ranging 0-10, were multiplied by ten. Subsequently, all VAS scores were log transformed due to skewness. The study by Marshall-McKenna (18) used the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) scored with Pain Rating Index (PRI), therefore the results from that study were not included.

Risk of bias (RoB)

The Cochrane RoB scale highlighted issues regarding allocation concealment, blinding, selective reporting, and other bias with all trials judged as “unclear” or “high” RoB in at least one or more criteria.

Effects of Myofascial therapy

MFT improved shoulder abduction by 13.0 degrees immediately after treatment (95% CI, 6.3 to 19.6; p=0.001) (Figure 1). The results were also statistically significant at follow up, with an average improvement of 10.4 degrees as compared with the controls (mean difference, 10.4; 95% CI, 3.0 to 17.8; p=0.006) (Figure 2). Meta-analyses on shoulder function and pain immediately after intervention were in favor of MFT (non-statistically significant) and had in both measures statistically significant treatment effect at follow up, where shoulder function improved (mean difference in DASH scores, -5.8; 95% CI, -10.7 to -1.0; p=0.020) (Figure 3), and pain intensity was reduced (mean difference in log transformed VAS, -0.33; 95% CI, -0.54 to -0.12; p=0.003) (Figure 4). The meta-analysis on shoulder flexion both immediately after intervention and at follow up showed non-statistically significant effect.

FIGURE 1

![Figure 1: Forest plot of comparison: Range of motion: Shoulder abduction immediately after intervention. A higher number indicates greater range of motion [degrees]. MFT, myofascial therapy, SD, standard deviation, CI, confidence interval.](https://image.fysioterapeuten.no/158023.webp?imageId=158023&x=0.00&y=0.00&cropw=100.00&croph=100.00&width=960&height=318&format=jpg)

FIGURE 2

![Figure 2: Forest plot of comparison: Range of motion: Shoulder abduction last follow up 1-9 months after intervention. A higher number indicates greater range of motion [degrees]. MFT, myofascial therapy, SD, standard deviation, CI, confidence interval.](https://image.fysioterapeuten.no/158025.webp?imageId=158025&x=0.00&y=0.00&cropw=100.00&croph=100.00&width=960&height=318&format=jpg)

FIGURE 3

![Figure 3: Forest plot of comparison: Shoulder function DASH (0-100), last follow up 1-9 months after intervention. A higher score indicates a greater disability. [points], MFT, myofascial therapy; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.](https://image.fysioterapeuten.no/158027.webp?imageId=158027&x=0.00&y=0.00&cropw=100.00&croph=100.00&width=960&height=288&format=jpg)

FIGURE 4

![Figure 4: Forest plot of comparison: Pain VAS last follow up 1-9 months after intervention. A higher score indicates a higher level of pain [log transformed at 0-4.6], MFT, myofascial therapy; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.](https://image.fysioterapeuten.no/158029.webp?imageId=158029&x=0.00&y=0.00&cropw=100.00&croph=100.00&width=960&height=336&format=jpg)

Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the impact of MFT on physical late effects in the upper body following surgery and radiotherapy in BC treatment. The results, encompassing four RCTs involving 245 participants, offer some support for the clinical effectiveness of MFT concerning specific aspects of ROM, shoulder function, and pain. These findings are in line with previous systematic reviews examining the effect of MFT (10,12) in postoperative rehabilitation and exercise programs (26,27) after BC treatment. Nevertheless, this systematic review also highlights the limited research on the effects of MFT in this specific patient group, and the included studies demonstrate methodological limitations. There is a need for further research to strengthen the evidence for the effectiveness of MFT. Consequently, the discussions in this review aim to stimulate further considerations of how these findings may impact real-world clinical practices and suggest future research directions.

The aim of MFT is to enhance the condition of tight skin and underlying soft tissue by improving the elastic properties of fascia. While the term “Myofascial” relates to the fascia surrounding muscles, MFT also influences fascia situated between other structures. “Fascia” is the web of tissues that connect all structures in the body, from the soft collagenous connective tissues like the innermost intramuscular layer of the endomysium, to the denser connective tissues, such as capsules and ligaments, and it also connects the peripheral nerves to its surrounding structures (28). The techniques that underlie the term “myofascial therapy,” such as “myofascial release” (10) and “myofascial induction” (21), have the same purposes, but lack clarity in practical application, and therefore posing challenges for both clinical practice and research.

Soft tissue undergoes changes during and after BC treatment due to natural healing and inflammatory processes related to surgery and radiotherapy (29,30). Post- operative complications such as infections and seroma could impact the post-operative healing process and increase the chances of fibrosis and rigid scar tissue development (31–33). However, the included studies did not provide information on post-operative complications, which can be considered as a methodological limitation, because knowledge about such complications is relevant in rehabilitation. A thorough pre-rehabilitation interview and ongoing monitoring throughout the rehabilitation period is crucial due to the continuous soft tissue changes (34). In clinical practice, strict standardized physiotherapy regimes are less ideal because of the risk of overburdening the fascia and soft tissue and thereby potentially cause more harm than good. Adjusting physiotherapy interventions to each patient is therefore crucial.

Exercise is recommended in BC treatment rehabilitation (11), but considerations of intensity, duration, and timing are essential for both MFT and exercise in respect to the patient’s treatment response. The diversity of intervention procedures for the controls in the included studies ranged from active exercise to local scar tissue treatment. This complicates determining the comparative effectiveness of MFT over the controls, as both groups were exposed to potential therapeutic interventions. Future well-designed studies with a guideline driven standard care for controls should avoid manual treatment techniques similar to MFT, and also describe the applied MFT techniques in detail. This may offer a more accurate measure of MFT effects.

Nerve damage is a common reason for upper-limb dysfunction and persisting pain post-BC treatment (35). As mentioned initially in this paper, the purpose of MFT is to improve conditions, not only in tight skin, but also in the surrounding structures of the peripheral nerves. While surgical procedures and radiotherapy undoubtedly are more refined today than in earlier years, they still affect muscles and nerves, influencing neural pathways, muscular activity and shoulder movement (35–37). Including nerve- and strength tests in outcome measures in clinical trials, could contribute in development of individual targeted treatment plans, containing exercises tailored for neuromuscular activity, and muscle control and strength. Nerve tests should encompass the brachial nerve, given its innervation of the surgical- and radiotherapy affected area. Strength tests should particularly focus on muscles such as the mm. pectoralis, serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi, with a primary emphasis on the axillary and scapular part i.e., activity in shoulder movement. This focus is essential, as these muscles are more susceptible to disturbances arising from BC treatment (36–38).

This systematic review comprised only a modest number of studies, exhibiting a varied risk of bias primarily due to poorly structured procedures in most of the included studies (15–17,19). All studies in this systematic review initiated interventions shortly after surgery or radiotherapy and had a relatively limited duration. Since late effects can manifest over time, becoming pronounced months or even years after BC treatment, a notable knowledge-gap exists regarding investigations into the long-term effects of MFT that exceeds nine months. The optimal timing for exercise and therapy, remain uncertain. Hence, there is a critical need for recommendations on timing, appropriate dosage, and treatment intensity of both MFT and exercise. The potential effects of MFT as a supplementary intervention to exercise in treating physical late effects in the affected upper body after BC treatment are still unclear. Essential for advancing this field are high-quality RCTs with larger participant numbers and reduced bias risk.

This study has some strengths and limitations. The criteria for inclusion of RCTs exclusively examining MFT, avoiding other manual techniques in the intervention group, is a procedural strength. However, limitations, such as the small number of studies, the varied risk of bias, not considering baseline measures in meta-analyses and excluding other study designs such as cross over studies, warrant caution in interpreting the results. Strengths of this systematic review includes using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses and the extensive and thoroughly executed literature searches confirming the positive effect of MFT also shown in other reviews (12,26,27).

In conclusion, this current evidence supports the effectiveness of MFT in addressing physical late effects after BC treatment, by increasing ROM in shoulder abduction, improving shoulder function, and reducing pain. However, there is a need for further research to elucidate optimal treatment parameters such as treatment timing, -frequency, intensity and -duration both regarding MFT and exercise, explore additional outcome measures, such as nerve function, and investigate a broader long-term effect of MFT including life quality.

References

1. Casla S, López-Tarruella S, Jerez Y, Marquez-Rodas I, Galvão DA, Newton RU, mfl. Supervised physical exercise improves VO2max, quality of life, and health in early stage breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internett]. 2015 [sitert 17. juni 2024];153(2):371–82. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1709714528?parentSessionId=G1a0um6z6eJLAowmIEzAb1UcRaS1tBCPqc0G8p1EDwY%3D&pq-origsite=primo&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

2. Jakobsen E. Kreftregisteret. 2024 [sitert 17. juni 2024]. Kreft i Norge. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/Temasider/om-kreft/

3. Stegink-Jansen CW, Buford WL, Patterson RM, Gould LJ. Computer Simulation of Pectoralis Major Muscle Strain to Guide Exercise Protocols for Patients After Breast Cancer Surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther [Internett]. juni 2011 [sitert 17. juni 2024];41(6):417–26. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2011.3358

4. Hayes SC, Johansson K, Stout NL, Prosnitz R, Armer JM, Gabram S, mfl. Upper-body morbidity after breast cancer. Cancer [Internett]. 2012 [sitert 17. juni 2024];118(S8):2237–49. Tilgjengelig på: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cncr.27467

5. Johansson K, Ingvar C, Albertsson M, Ekdahl C. Arm Lymphoedema, Shoulder Mobility and Muscle Strength after Breast Cancer Treatment – A Prospective 2-year Study. Adv Physiother [Internett]. mai 2001 [sitert 17. juni 2024];3(2):55–66. Tilgjengelig på: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=4645231&scope=site

6. Lauridsen MC, Overgaard M, Overgaard J, Hessov IB, Cristiansen P. Shoulder disability and late symptoms following surgery for early breast cancer. Acta Oncol [Internett]. 1. januar 2008 [sitert 17. juni 2024];47(4):569–75. Tilgjengelig på: https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860801986627

7. Askoxylakis V, Jensen AD, Häfner MF, Fetzner L, Sterzing F, Heil J, mfl. Simultaneous integrated boost for adjuvant treatment of breast cancer- intensity modulated vs. conventional radiotherapy: The IMRT-MC2 trial. BMC Cancer [Internett]. januar 2011 [sitert 17. juni 2024];11(1):249–56. Tilgjengelig på: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=63888511&scope=site

8. Levangie PK, Drouin J. Magnitude of late effects of breast cancer treatments on shoulder function: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internett]. juli 2009 [sitert 17. juni 2024];116(1):1–15. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/212475772/abstract/1AA1083E9BE24769PQ/1

9. Riaz N, Jeen T, Whelan TJ, Nielsen TO. Recent Advances in Optimizing Radiation Therapy Decisions in Early Invasive Breast Cancer. Cancers [Internett]. januar 2023 [sitert 31. mars 2023];15(4):1260. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/15/4/1260

10. Ajimsha MS, Al-Mudahka NR, Al-Madzhar JA. Effectiveness of myofascial release: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther [Internett]. 1. januar 2015 [sitert 23. april 2023];19(1):102–12. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1360859214000862

11. Nesvold IL, Frantzen TL, Tagholdt KL. Fysioterapi til Kreftpasienter [Internett]. Norsk Fysioterapiforbund; 2016. Tilgjengelig på: https://25892275.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/25892275/Fysioterapi%20til%20kreftpasienter.pdf

12. Pinheiro da Silva F, Moreira GM, Zomkowski K, Amaral de Noronha M, Flores Sperandio F. Manual Therapy as Treatment for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Female Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther [Internett]. 1. september 2019 [sitert 23. april 2023];42(7):503–13. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0161475418302628

13. Higgins JPT, White IR, Anzures-Cabrera J. Meta-analysis of skewed data: Combining results reported on log-transformed or raw scales. Stat Med [Internett]. 2008 [sitert 17. juni 2024];27(29):6072–92. Tilgjengelig på: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/sim.3427

14. Higgins J, Savović J, Page M, Sterne J. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. I: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 64 [Internett]. 6. utg. Cochrane; 2023 [sitert 17. juni 2024]. Tilgjengelig på: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-08

15. De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Verlvoesem N, Dieltjens E, Vos L, De Vrieze T, mfl. Effect of myofascial techniques for treatment of upper limb dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors: randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer [Internett]. juli 2017 [sitert 17. juni 2024];25(7):2119–27. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1902403995/abstract/A96E437579284472PQ/1

16. De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Vervloesem N, De Geyter S, Christiaens MR, Neven P, mfl. Myofascial techniques have no additional beneficial effects to a standard physical therapy programme for upper limb pain after breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil [Internett]. 1. desember 2017 [sitert 17. juni 2024];31(12):1625–35. Tilgjengelig på: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517708605

17. De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Vervloesem N, Dieltjens E, Christiaens MR, Neven P, mfl. Effect of myofascial techniques for treatment of persistent arm pain after breast cancer treatment: randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(4):451–61.

18. Marshall-McKenna R, Paul L, McFadyen AK, Gilmartin A, Armstrong A, Rice AM, mfl. Myofascial release for women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer: A pilot study. Eur J Physiother [Internett]. 1. mars 2014 [sitert 17. juni 2024];16(1):58–64. Tilgjengelig på: https://doi.org/10.3109/21679169.2013.872184

19. Serra-Añó P, Inglés M, Bou-Catalá C, Iraola-Lliso A, Espí-López GV. Effectiveness of myofascial release after breast cancer surgery in women undergoing conservative surgery and radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer [Internett]. juli 2019 [sitert 17. juni 2024];27(7):2633–41. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2137067373/abstract/E9D11FB4C1B544DAPQ/1

20. Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C, Moral-Avila R del, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Feriche-Fernández-Castanys MB, Arroyo-Morales M. Effectiveness of Core Stability Exercises and Recovery Myofascial Release Massage on Fatigue in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Saad B, redaktør. Evid - Based Complement Altern Med [Internett]. 2012 [sitert 17. juni 2024];2012. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2060805707/abstract/8EBD7CD72EBF41CDPQ/1

21. Castro-Martín E, Ortiz-Comino L, Gallart-Aragón T, Esteban-Moreno B, Arroyo-Morales M, Galiano-Castillo N. Myofascial Induction Effects on Neck-Shoulder Pain in Breast Cancer Survivors: Randomized, Single-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Design. Arch Phys Med Rehabil [Internett]. 1. mai 2017 [sitert 17. juni 2024];98(5):832–40. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003999316313132

22. Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Cuesta-Vargas A i., Fernández-Delas-Peñas C, Arroyo-Morales M. Attitudes towards massage modify effects of manual therapy in breast cancer survivors: a randomised clinical trial with crossover design. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) [Internett]. 2012 [sitert 17. juni 2024];21(2):233–41. Tilgjengelig på: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01306.x

23. Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Sánchez-Salado C, Arroyo-Morales M. The Influence of Patient Attitude Toward Massage on Pressure Pain Sensitivity and Immune System after Application of Myofascial Release in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized, Controlled Crossover Study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther [Internett]. 1. februar 2012 [sitert 17. juni 2024];35(2):94–100. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0161475411002296

24. Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, del Moral-Ávila R, Castro-Sánchez AM, Arroyo-Morales M. Effectiveness of a Multidimensional Physical Therapy Program on Pain, Pressure Hypersensitivity, and Trigger Points in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin J Pain [Internett]. februar 2012 [sitert 17. juni 2024];28(2):113. Tilgjengelig på: https://journals.lww.com/clinicalpain/abstract/2012/02000/effectiveness_of_a_multidimensional_physical.4.aspx

25. Rangon FB, Koga Ferreira VT, Rezende MS, Apolinário A, Ferro AP, Guirro EC de O. Ischemic compression and kinesiotherapy on chronic myofascial pain in breast cancer survivors. J Bodyw Mov Ther [Internett]. 1. januar 2018 [sitert 17. juni 2024];22(1):69–75. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S136085921730092X

26. De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Dieltjens E, Christiaens MR, Neven P, Geraerts I, mfl. Effectiveness of Postoperative Physical Therapy for Upper-Limb Impairments After Breast Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(6):1140–53.

27. McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, Rowe BH, Dabbs K, Klassen TP, mfl. Exercise interventions for upper‐limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internett]. 2010 [sitert 23. april 2023];(6). Tilgjengelig på: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005211.pub2/abstract

28. Schleip R, Jäger H, Klingler W. What is ‘fascia’? A review of different nomenclatures. J Bodyw Mov Ther [Internett]. 1. oktober 2012 [sitert 13. september 2023];16(4):496–502. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1360859212001830

29. Milliat F, François A, Isoir M, Deutsch E, Tamarat R, Tarlet G, mfl. Influence of Endothelial Cells on Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Phenotype after Irradiation: Implication in Radiation-Induced Vascular Damages. Am J Pathol [Internett]. 1. oktober 2006 [sitert 29. juni 2023];169(4):1484–95. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002944010626156

30. Stone HB, Coleman CN, Anscher MS, McBride WH. Effects of radiation on normal tissue: consequences and mechanisms. Lancet Oncol [Internett]. september 2003 [sitert 29. juni 2023];4(9):529–36. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/200898654/abstract/1B43635B2D6449FPQ/1

31. Douay N, Akerman G, Clément D, Malartic C, Morel O, Barranger E. Seroma after axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer. Gynécologie Obstétrique Fertil [Internett]. februar 2008 [sitert 20. august 2023];36(2):130–5. Tilgjengelig på: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1297958907005498

32. Lotfy WE, Mohamed OAA, Elhady LM, Abuojaylah MA. An Overview of Post Mastectomy Seroma and Treatment Options: Review Article. Egypt J Hosp Med [Internett]. 1. juli 2022 [sitert 20. august 2023];88(1):2568–70. Tilgjengelig på: https://ejhm.journals.ekb.eg/article_239192.html

33. Kim S, Kim YS. Radiation-induced osteoradionecrosis of the ribs in a patient with breast cancer: A case report. Radiol Case Rep [Internett]. 1. august 2022 [sitert 20. august 2023];17(8):2894–8. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S193004332200067X

34. Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, Momeni A, Longaker MT, Wan DC. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg [Internett]. oktober 2019 [sitert 23. april 2023];83(4):S59–64. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6746243/

35. Joshi D, Shah S, Shinde SB, Patil S. Effect of Neural Tissue Mobilization on Sensory-Motor Impairments in Breast Cancer Survivors with Lymphedema: An Experimental Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 1. januar 2023;24(1):313–9.

36. Rasmussen GHF, Kristiansen M, Arroyo-Morales M, Voigt M, Madeleine P. Absolute and relative reliability of pain sensitivity and functional outcomes of the affected shoulder among women with pain after breast cancer treatment. PLoS One [Internett]. juni 2020 [sitert 26. juni 2023];15(6):e0234118. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2409182283/abstract/4AEB7FE699C3483EPQ/1

37. Leonardis JM, Lulic-Kuryllo T, Lipps DB. The impact of local therapies for breast cancer on shoulder muscle health and function. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol [Internett]. september 2022 [sitert 22. august 2023];177:103759. Tilgjengelig på: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1040842822001834

38. Paolucci T, Capobianco SV, Bai AV, Bonifacino A, Agostini F, Bernetti A, mfl. The reaching movement in breast cancer survivors: Attention to the principles of rehabilitation. J Bodyw Mov Ther [Internett]. oktober 2020 [sitert 21. juni 2023];24(4):102–8. Tilgjengelig på: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1360859220301182

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2025. Re-use permitted under CC BY-NC. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Published by Fysioterapeuten.